Where did those rustic rock buildings in many Texas State Parks come from — the ones that look so natural, they might simply have grown out of the ground? They might be visitor centers, group shelters or cabins. Chances are that those structures were built by young men in the Civilian Conservation Corps during the 1930s and early 1940s.

The CCC developed 56 state, national and local parks in Texas between 1933 and 1942. Thirty-one of these are still in the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department. Other parks serve the public in cities and counties around the state.

Born of a national economic emergency, the CCC was organized in the wink of an eye, lived a short but productive nine years, then was allowed to die. Here is its story, including its impact on Texas and Texans.

Why the CCC Was Formed: The Great Depression

Texas has lived through a number of economic disasters, but none was so thoroughly devastating as the Great Depression. There were many contributing factors to the Depression, but the precipitating event was the stock market crash in late October 1929 and the subsequent run on banks as people scrambled to get their money out of failing institutions. The bottom fell out of the economies of not only the United States, but also European countries and most other developed countries of the world.

President Herbert Hoover was slow to acknowledge the scope of the Depression. He rejected recommendations of direct aid to Americans, believing the problem was simply a cyclical swing that could be remedied by “voluntary cooperation” between business and government, with business taking the lead. Since no businesses were willing to take the risks necessary for such a scheme to have a chance to work, Hoover’s plan failed.

By the 1932 presidential election, unemployment was rampant, soup lines were long, agricultural prices were hitting bottom, and Americans were desperate for drastic remedies that only the government could put into action.

New York Governor Franklin Delano Roosevelt handily won the presidency in 1932. Sworn into office on March 4, 1933, Roosevelt quickly pushed a package of legislation, termed the “New Deal,” through Congress setting up myriad new federal agencies to funnel direct payments to suffering Americans. Most were designed to provide work on specially created government projects. Each agency targeted a particular segment of the economy — agriculture, industry, local jobs, the arts — with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation insuring banks against losses.

The CCC was created to employ young single men from ages 18 to 25 on outdoor conservation projects. Originally called Emergency Conservation Work, the agency was dubbed the Civilian Conservation Corps by the press and that name became official in 1937.

The minimum age was dropped to 17 later, and the maximum fluctuated, going as high as 28. Two-thirds of CCC enrollees were 20 or younger. They had to be physically fit and come from families that were on relief and to whom they were willing to send most of their pay. Each man earned $30 per month, of which $25 went directly to his family (the average CCC enrollee came from a family of eight). The large public projects were mainly in rural areas so that the CCC’s low wages would not compete unfairly with private businesses.

President Roosevelt signed the enabling legislation on March 31, 1933, naming Robert Fechner, a former machinists’ union leader, director of the agency.

On April 17, 1933, an incredibly fast two-and-a-half weeks after Roosevelt signed the legislation, the first enrollees arrived at the first CCC camp, appropriately named Camp Roosevelt, in the George Washington National Forest near Luray, Virginia. By July 1, more than 270,000 enrollees were living in 1,330 camps across the country.

During its nine-year existence, the CCC distributed more than $2.4 billion in federal funds to employ more than 2.5 million jobless young men (up to 519,000 were enrolled at any one time) who worked in about 3,000 camps.

In the agency’s first five years, enrollees planted more than 1.3 billion tree seedlings, most in forests that had been clear cut and abandoned. They erected fire towers, built truck roads and firebreaks, reclaimed thousands of acres of land from soil erosion, and constructed facilities for visitors to national forests. They also developed national, state and local parks.

The Civilian Conservation Corps was probably the most popular and successful of the New Deal agencies. It employed thousands of idle young men and trained them in useful jobs. Their work provided money for their families, as well as income for businesses near CCC camps, where CCC administrators purchased camp supplies. The enrollees taught farmers how to prevent soil erosion, and they left a legacy of forest and park improvements all over the nation that Americans continue to enjoy today.

Organization of the CCC

In order to enroll, check qualifications of, train, clothe, feed, house and transport a large number of young men in a short time, Roosevelt called on the only government agency that had the capacity and experience to do it: the U.S. Army. Their clothing was leftover World War I uniforms. Initial housing on project sites was Army tents, replaced as soon as practicable by enrollee-built barracks, mess halls and support buildings. These were, in turn, replaced by portable, reusable buildings after 1935.

A regular Army officer was appointed commander of each camp, with reserve officers assisting. After December 1933, reserve officers replaced regular officers as commanders, with specially trained enrollees assisting.

The Army divided the United States into nine “corps areas.” Texas shared the Eighth Corps Area with Oklahoma, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado and most of Wyoming, with headquarters at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio.

Local relief agencies handled recruitment, following federal guidelines and overseen by the U.S. Department of Labor. The forest and soil-conservation projects were supervised by the U.S. Department of Agriculture; park development was coordinated by the National Park Service of the Interior Department. Classes were planned by the U.S. Office of Education. The CCC Advisory Council, composed of a representative from each of these agencies and the Army, helped the director set policy and guided the work of the CCC. State relief agencies were responsible for suggesting projects and providing direct supervision of the work. Each CCC camp also hired “local experienced men” to help train enrollees in such vital skills as how to handle tools.

Such a complex administrative organization, with responsibility shared among many agencies at several levels of government, would appear to be, as one writer called it, a “bureaucratic monstrosity.” But historian Mark Welborn explains that each agency had specific duties, and a workable communication network was in place. For the most part, the plan worked reasonably well for the limited time that it was needed.

Camps were set up in every state plus Alaska, Hawaii (both U.S. territories at the time), Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. When a camp completed work on one project, it might be moved to another location, so enrollees often worked in several different locations during their time in the CCC.

Soil conservation and forest management projects were on both public and private lands.

The original goal was to enroll 250,000 youths at a time for six-month periods, allowing them to re-enroll for an additional six months. Later, the re-enrollment period was lengthened to one year, and the boys could sign up for more than one extension.

Segregation at the Camps

The CCC was of very limited assistance to black families during the Depression, because of local bigotry and national CCC leaders’ political concerns. CCC rules forbade discrimination based on race, color or creed, but local relief boards often refused to enroll blacks, particularly in the South. The political realities of the time included white enrollees’ hostility to blacks being in the same camps. When they were enrolled, blacks were almost always placed in segregated camps, not only in the South, but all over the country.

In Texas camps, there was nominal integration for a couple of years, but those camps maintained segregated barracks, mess halls, latrines and recreation halls. During these years, the total number of blacks accepted by Texas CCC recruiters was only 300. After a number of ugly racial incidents, separate black camps were instituted throughout the entire CCC in 1935.

Also, when the camps in white enrollees home states were filled, they were sent to other states whose camps were not yet at capacity. Blacks were not. They were enrolled only as vacancies occurred in black camps within their home states.

By 1935, the percentage of black enrollment in Texas was finally equal to their percentage of the population. But because a larger percentage of blacks than whites were poor, they were not able to participate in proportion to their need.

The main reason administrators and camp commanders gave for not enforcing integration of camps as required by law was that the only purpose of the CCC was to provide work for the enrollees rather than to fight for civil rights.

In April 1933, President Roosevelt authorized the CCC to enroll 14,000 American Indians. They mainly served at separate camps located on 50 million acres of tribal lands in 23 states, helping mitigate the effects of a severe drought.

The following month, the president ordered the enrollment of up to 25,000 World War I veterans. They also served at separate camps.

The Texas Relief Agencies

Governor Miriam “Ma” Ferguson persuaded the Legislature to create the Texas Rehabilitation and Relief Commission in spring 1933 to coordinate the state’s efforts with Roosevelt’s relief plans.

Lawrence Westbrook was director of Texas’ CCC selection process, but much of the work until 1937 was done by assistant director Neal Guy. The forest projects were coordinated by E.O. Siecke of the State Forest Service, and State Parks Board director Wendall Mayes handled parks projects.

At its peak of operations, 96 Texas CCC camps employed about 19,200 men at a time. Although the CCC’s parks work is best known to the public, most of the Texas CCC camps did soil-conservation and erosion-control work.

Life in the CCC

On acceptance, enrollees were sent to “conditioning camps” at army posts for about two weeks, where they learned to function as a group and began intense physical exercise. From there they went to individual camps, which housed about 200 men each.

The day usually started with reveille at 6 or 6:30 a.m. Morning exercises were followed by a hearty breakfast, plain but ample. After straightening the barracks and policing the camp, they went to the work site by 8 a.m. for an eight-hour day of hard physical labor. Lunch was brought to the site about 1 p.m. The workday ended about 4 p.m., with supper back at camp by 5 or 5:30 p.m., followed by leisure activities — sports, games or reading. Lights out was at 10:30 p.m.

Most of the camps had libraries, as well as sports programs, which might include baseball, softball, boxing and football, and other recreation for filling after-work hours. For example, several enrollees at the Hereford camp formed an orchestra, aided by a few townspeople. The Palo Duro camp held a semi-monthly dance. A number of camps produced their own newsletters.

Education of the CCC Enrollees

Discovering that many of the enrollees were functionally illiterate, the CCC enlisted the help of the U.S. Office of Education to provide classes in basic school subjects — English, spelling, arithmetic and writing — and vocational courses. A camp education specialist taught some classes; others might be taken at nearby high schools. Additional courses might include radio, shorthand or geometry, as at the Brenham camp. Enrollees at Longhorn Cavern could choose from dramatics, debate, social sciences, typing, singing, mechanical drawing and penmanship. Classes at Palo Duro Canyon included not only basic academics, but also such extras as one enrollee giving “a very interesting and enlightening talk on the curing of fresh pork …”

Nationally, by June 1937, 35,000 men had learned to read and write, more than 1,000 received the equivalent of a high-school education, and 39 had received college degrees.

The CCC Creates Parks

Texas had a State Parks Board that by 1933 had acquired several historical sites and received a few gifts of land for parks, but it had no funds to develop and maintain a park system. As did other states, Texas seized the opportunity to create a large number of state parks using CCC labor and federal relief funds. The first four CCC park camps in Texas were at the Davis Mountains, Caddo Lake, Blanco and Mineral Wells.

Texas Canyons State Park was one of those planned in 1933 and was to be built in West Texas on a strip of land along the Rio Grande encompassing several canyons. Later that year, the Chisos Mountains were added to the acreage, and the name was changed to Big Bend State Park. A CCC camp began developing the park in 1935. The transfer to federal ownership was made in 1942; it opened as Big Bend National Park in 1944.

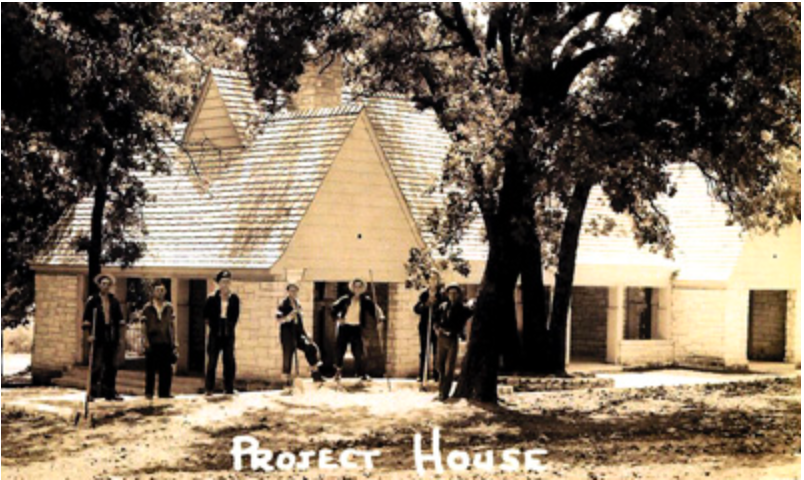

Between 1933 and 1942, CCC enrollees built lodges, cabins, picnic pavilions, refectories, concession buildings, support buildings, footbridges and restrooms, usually from native rock and timber. They also constructed swimming pools, strung telephone lines, planted thousands of trees, developed hiking and equestrian trails, installed guardrails, built dams to impound lakes, and constructed culverts to provide drainage.

Some Texas parks presented particular challenges: At Davis Mountains State Park, enrollees molded adobe bricks to build Indian Lodge. At Longhorn Cavern, the campers dug more than 2 million cubic yards of silt and bat guano out of the cave. The rock that they also removed was used to construct bridges and entrance gates to the park and the cavern. CCC enrollees at the Balmorhea camp built a huge, one-and-three-quarter-acre swimming pool. Still in use, the pool is 25 feet deep and is filled by San Solomon Springs’ 72-degree-to-76-degree water.

The men were also on hand to help with emergencies. In 1935, enrolleees in the Big Spring camp saw a fire on Scenic Mountain. When enrollee James Cook of Plainview ran to the location, he saw, “a group of women standing by a flaming automobile trying to put the fire out with screams …” The boys phoned for a wrecker.

National Forests in Texas

When the Great Depression began, Texas had no national forests. In 1933, the Texas Legislature authorized the sale of lands in East Texas to the federal government for the development of national forests, and the land transfer was formalized in 1936. The CCC developed Texas’ national forests: Davy Crockett, Angelina, Sam Houston and Sabine, which today cover 637,646 acres in parts of 12 Texas counties.

In them, the CCC reforested bare areas; erected lookout towers, water towers and observation platforms; fought forest fires; waged war against tree insects and diseases; and developed campgrounds.

Soil Conservation Work

The Great Depression coincided with the Dust Bowl across the Great Plains, adding agricultural woes to the general economic ones. Settlers had moved onto the plains in the late 19th century and plowed up most of the native grasses to raise crops. When the crops failed because of severe drought beginning in the early 1930s, there was no vegetation to hold the dirt when windstorms hit the area. Loose dirt picked up in the Great Plains was carried sometimes for thousands of miles. The “dusters” turned daylight into dark, making it hard to see more than a few feet and making it even harder to breathe. Amarillo residents, for example, counted more than 190 “black blizzards” between January 1933 and February 1936. The storms that boiled across the denuded plains for almost a decade gave the afflicted area the name “Dust Bowl.”

While the arid plains were blowing away, farmers farther east had a different soil problem. In Central Texas, land that once produced 200 to 300 pounds of lint cotton per acre annually yielded only 100 to 150 pounds in 1935. Farmers assumed that the soil had simply worn out. But much of their trouble stemmed from the common practice of planting crops in long, straight rows, creating ideal conditions for soil erosion. The March 1935 issue of Farm and Ranch magazine stated that between 1930 and 1935, loss of topsoil was as great as 65 tons per acre where corn had been grown in rows running up and down slopes. The land was not wearing out, it was washing away.

CCC enrollees, guided by the Soil Conservation Service of the Department of Agriculture, taught 5,000 Texas farmers how to terrace their fields and use contour plowing to prevent soil loss by holding rain in place until it soaked into the dirt rather than letting it run off, carrying valuable topsoil with it.

The work of the Memphis SCS camp, opened in July 1935, was typical. Working in parts of four surrounding Texas counties, the campers surveyed contour lines and laid terraces, seeded range land, and built stock tanks and dams.

They constructed 130 miles of terraces, 1,500 check dams, and 16 stock tanks; furrowed 1,500 acres of pasture; and planted 20 miles of trees and shrubs.

The CCC at the Texas Centennial

The National Park Service and the Texas State Parks Board sponsored an extensive CCC exhibit at Fair Park in Dallas during the Texas Central Centennial Exposition, June 6 to November 29, 1936, celebrating the Texas Centennial. Around a 28,000-square-foot area, CCC enrollees erected a wall of native stone and timber. Within it, they built a weekend cabin, like the ones built in Texas State Parks, and a fieldstone and pine-log building to display exhibits by the federal agencies involved in the CCC program.

The exhibit building’s rustic front door swung on large wrought-iron hinges made at the White Rock Lake CCC camp. Examples of furniture used in park cabins, handmade from Texas cedar by enrollees at Palo Duro Canyon, were part of the exhibit. Twenty-four CCC members guided visitors through the exhibit.

In the courtyard, enrollees planted a miniature forest composed of 85 varieties of native trees and shrubs from all over the state, from the mesquite and catclaw of Southwest Texas to the magnolias, pines and dogwoods of East Texas.

The Final Days of the CCC

As the Depression eased and businesses began hiring, the CCC had increasing problems attracting and keeping enrollees. Some signed up but deserted if they didn’t like the work or if they found a job in the private sector. With the threat of war in Europe looming, other potential CCC members signed up for military service instead. Some CCC camps began substituting military-related training for education: demolition, road and bridge construction, radio operation, first aid and cooking.

The number of camps and enrollees continued shrinking until Congress finally ended the CCC on June 30, 1942.

A total of 156,000 Texans were enrolled in the CCC during its nine years of existence, according to historian Mark Welborn. (Other writers say 50,000, the difference perhaps resulting from one writer counting an enrollee each time he re-enrolled, and another counting each individual only once.) Many of the enrollees entered the CCC undernourished and dejected. Almost to a man, they gained strength, confidence and weight, gaining an average 11¼ pounds. For the most part, CCC alumni look back on their experiences fondly. As E. Maury Wallace of Austin, who worked on Longhorn Cavern, said in 1988: “[We] were just hard up for work. I was glad to get a job. We ate good every day and you could have all you wanted.” In 2005, an alumnus of the Garner State Park camp remembered his pride in being able to pay his mother’s way through beauty school with the allotment he sent home.

Former CCC enrollees have organized the National Association of Civilian Conservation Corps Alumni (NACCCA), which holds an annual meeting (the 2006 meeting was in Dallas). Some local alumni chapters exist, as well.

The immediate purpose of the CCC was to provide a living for destitute young men and their families, but the relief funds benefited all of Texas. Texans continue to enjoy the results of the hard work of this extraordinary group of young men.

— written by Mary G. Ramos, editor emerita, for the Texas Almanac 2008–2009

Sources

Brophy, William J. “Black Texans and the New Deal,” The Depression in the Southwest. Donald W. Whisenhunt, ed. National University Publications, Port Washington, N.Y., 1980.

Cox, Jim. “Fond Memories from a Time of National Hardship.” Texas Parks and Wildlife Magazine, September 1978. Reprinted online at http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/spdest/findadest/historic_sites/ccc/; accessed Nov. 3, 2005.

Dallas Morning News, various. “Park Service Installing Fair Exhibit,” April 19, 1936; “Trees From All Parts of Texas Viewed at Fair,” June 7, 1936; “Trying Out C.C.C. Furniture,” June 21, 1936.

Hendrickson, Kenneth E., Jr. “Replenishing the Soil and the Soul of Texas: The CCC in the Lone Star State as an Example of State-Federal Work Relief During the Great Depression.” Faculty Papers, Series 2, Vol. 1, Midwestern State University, Wichita Falls, Texas, 1974–1975.

“Index of States/Camps Listing: Texas.” National Association of Civilian Conservation Corps Alumni (NACCCA) website: http://www.ccclegacy.org/index.htm; accessed Jan. 19, 2007.

Lacy, Leslie Alexander. The Soil Soldiers: The Civilian Conservation Corps in the Great Depression. Chilton Book Company, Radnor, Pa., 1976.

Merrill, Perry H. Roosevelt’s Forest Army: A History of the Civilian Conservation Corps, 1993–1942. Perry H. Merrill, Montpelier, Vt., 1981.

Mortimer, John L. “Farmers to Control Soil Erosion.” Farm and Ranch, Farm and Ranch Publishing Co., Dallas, March 15, 1935.

Nall, Garry L. “The Struggle to Save the Land: The Soil Conservation Effort in the Dust Bowl,” The Depression in the Southwest. Donald W. Whisenhunt, ed. National University Publications, Port Washington, N.Y., 1980.

Otis, Alison T., et al. The Forest Service and The Civilian Conservation Corps: 1933–42. Forest Service, FS-395, U.S. Department of Agriculture, August 1986.

Paige, John C. The Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Park Service, 1933–1942: An Administrative History. The National Park Service, Department of the Interior, 1985. Online edition: http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/ccc/ccct.htm; accessed Jan. 8, 2007.

Plainsman, The, Vol. 1, No. 2, Lubbock, Aug. 16, 1935.

Rodgers, L.W. “Civilian Conservation Corps Educational Program,” Texas Centennial Magazine. Texas Centennial Publishing Co., San Antonio, March 1936.

Salmond, John A. The Civilian Conservation Corps, 1933–1942: A New Deal Case Study. Duke University Press, Durham, N.C., 1967.

Steely, James Wright. The Civilian Conservation Corps in Texas State Parks. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Austin, 1986.

Steely, James Wright. Parks for Texas: Enduring Landscapes of the New Deal. University of Texas Press, Austin, 1999.

Sypolt, Larry N. Civilian Conservation Corps: A Selectively Annotated Bibliography. Praeger, Westport, Conn., 2005.

Texas Almanac, various. “Texas State Parks,” Texas Almanac 1936; “Texas State Parks — Public Recreation,” Texas Almanac 1941–42; “National Forests and Grasslands in Texas,” Texas Almanac 2006–2007. The Dallas Morning News, Dallas, Texas.

Welborn, Mark Alan. “Texas and the CCC: A Case Study in the Successful Administration of a Confederated State and Federal Program.” Master’s Thesis, University of North Texas, 1989.