In November 1830, Colonel Juan Davis Bradburn, a Kentuckian serving in the army of Mexico, chose a bluff overlooking the mouth of the Trinity River as the site of a new town and a fort. The place was to be called Anahuac, after the ancient home of the Aztecs. It was one of six outposts that the Mexican government planned to build at strategic entries into Texas. The site that Bradburn chose was just across Galveston Bay from the plain where the Battle of San Jacinto would be fought in April 1836.

The six forts and their garrisons were designed to enforce the Law of April 6, 1830 — passed only seven months before Colonel Bradburn arrived on his bluff – which was as repugnant to some of the Anglo colonists of Texas as England's Stamp Act had been to their forebears on the eve of the American Revolution. And it would have much the same effect.

In 1832, Texian anger at Colonel Bradburn's efforts to enforce the law would boil into an armed conflict that many consider the opening skirmishes of the Texas Revolution. One of the principal instigators of the conflict was a young lawyer recently arrived from Alabama named William Barret Travis, who four years later would die as Texian commander of the Alamo. (Texans in this period were generally called Texians.)

Unearthing the Ruins

Until recently, the remains of Fort Anahuac, where much of this Texian version of the Boston Tea Party occurred, had been almost lost to history. Some residents of Chambers County knew approximately where the fort had been, but nearly all vestiges of it had disappeared. During the past few years, however, systematic archaeological work by the Texas Historical Commission and a private firm hired by Chambers County has uncovered the foundations and other remains of the old post. The county now has ambitious hopes to preserve the things that have been found and to develop a museum and historical park around them. This would allow tiny Anahuac to join the Alamo, Goliad and Gonzales among the shrines of Texas independence.

Among the intents of the Law of April 6, 1830, which Colonel Bradburn had come to the Texas coast to enforce – and they were several – were to increase the Mexican military presence in Texas, prohibit the further importation of slaves into Texas, collect duties on imports into the Anglo colonies, void colonization contracts that had not yet been fulfilled, and (most onerous of all from the Texian point of view) curtail the flow of immigrants into Texas from the United States, many of whom were coming illegally. Fearing the presence of so many rambunctious Americans within its national borders, the Mexican government hoped to populate its vast, nearly empty northern territory with Mexicans and Europeans instead.

Bradburn also was ordered to inspect land titles (the illegals among the Texian settlers had none) and issue licenses to lawyers (which an amazing number of the Texians claimed to be).

Upon his arrival, the colonel and his soldiers built a temporary wooden fort near the site of the present Chambers County courthouse. It comprised a barracks, a guardhouse and quarters for Bradburn. Heavy rains prevented immediate construction of the permanent fort, so Bradburn's soldiers spent their time digging clay for the future manufacture of bricks. Construction of the permanent post finally began in March 1831.

Bradburn's Poor Start

From the beginning, the colonel and the Texians didn't get along. For the past decade, the larger Mexican nation had been preoccupied with its own revolution, political turmoil and civil war and had ignored the Anglo settlers on its far-off northern frontier. The Americans had become accustomed to the absence of Mexican governmental authority and enjoyed their freedom from it. Now, suddenly, it seemed that the government had come to apply a despotic boot to the Texians' necks. The Texians were quick to take umbrage at any number of real, imagined and fictitious offenses committed by Bradburn and his soldiers.

Although Bradburn apparently was trying only to fulfill the duties his government required of him, his public-relations skills were disastrous. Almost immediately after his arrival, he questioned the right of the land commissioner, who had been appointed by the state, to issue titles to some settlers who the colonel believed to be mere squatters.

Ship captains objected to Bradburn's insistence that all ships about to enter Galveston Bay had to make their way to Anahuac first for customs inspection. Anahuac was out of the way of the main shipping lanes, and the waters that had to be navigated to reach it were treacherous. Coastal merchants resented the very existence of the tariffs, which they had never had to pay before. Also, Bradburn demanded to see the licenses of all lawyers, since there were so many men in Texas who claimed to be lawyers who really were not.

Arrests and a Mysterious Man

But the spark that ignited the settlers' discontent into armed rebellion was Bradburn's arrest and imprisonment of Patrick Jack, William Travis' law partner.

Jack, a firebrand much like Travis, helped organize a local vigilante group and was elected its captain. Ostensibly, the purpose of this irregular force was to defend the settlement against Indians, but its real purpose, its members acknowledged privately, was to oppose the Mexicans. Since under the law only Bradburn had the authority to organize a militia, he arrested Jack, whose imprisonment inspired such fury among the settlers that Bradburn eventually had to release him. Jack's supporters welcomed him back with a public ceremony that ridiculed Bradburn.

Travis launched a campaign to further undermine the colonel's authority. When a few escaped slaves from Louisiana showed up in Anahuac, Bradburn declared them free men and enlisted them as soldiers in his garrison. This infuriated local slave owners. (Slavery was illegal in Mexico, but under Stephen Austin's agreement with an earlier government, Americans had been permitted to bring their slaves into Texas as "indentured servants.") About the same time, eight American mutineers from a New Orleans ship were captured by Mexican soldiers and imprisoned at Anahuac. Travis wrote inflammatory letters to the New Orleans newspapers protesting both these actions.

One night a mysterious, tall man, his face hidden in a cloak, slipped a letter to one of Bradburn's soldiers, warning the colonel that 100 Louisianans were marching toward Anahuac to retrieve the escaped slaves. Bradburn sent out his cavalry to scour the countryside for them, but the soldiers found no one. When the colonel realized the letter was a hoax, he suspected Travis to be the man in the cloak. He arrested and imprisoned him. When Patrick Jack protested his friend's arrest, Bradburn imprisoned him, too.

Texian Opposition Grows

The conflict between Bradburn and the Texians began to resemble an Errol Flynn movie, full of alarms and excursions: mobs marched, Texians from other communities headed to Anahuac to join the fray, Bradburn made more arrests, women and children fled. Eventually the Fort Anahuac guardhouse held 15 prisoners.

Meanwhile, the Texians ambushed the 19 cavalrymen that Bradburn had sent out to find them and made prisoners of them all. In negotiation, the Texians and Bradburn agreed that the soldiers would be released in exchange for Bradburn's prisoners. The Texians kept their end of the bargain; Bradburn did not.

A crowd of outraged settlers gathered on Turtle Bayou, not far from Fort Anahuac, to form an army to rescue their imprisoned friends. The rebels also drew up a set of resolutions, detailing their grievances against Bradburn and aligning themselves with Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna's Federalist faction in its struggle against the despotic Centralist government of Mexican President Bustamante, thus giving their actions a larger-than-local political focus. (Bradburn, of course, was an officer of the Centralist government.)

While the Texians were writing their resolutions, Bradburn strengthened his fort and sent a messenger to his commanding officer, Colonel Jose de las Piedras, at Nacogdoches to ask for help. When Piedras came riding to the rescue, a large rebel force intercepted him and his men. Fearing that he did not have a force strong enough to defeat the Texians, he capitulated to their demand and agreed to release Bradburn's prisoners and remove the colonel from his command.

On July 1, 1832, Bradburn turned over his troops to his second-in-command, Lt. Juan Cortina, and, fearing for his life, fled into the woods, hiding in creek bottoms and corncribs until he reached New Orleans. Americans who had sided with him during the disturbances – called "Tories" by the rebels – also were driven out of Anahuac, some of them tarred and feathered. By July 23, all Mexican troops had evacuated, and Fort Anahuac was vacant. Soon afterward, someone set fire to it and destroyed its wooden parts.

Three years later, in June 1835, the Mexican government (now run by Santa Anna) again sent troops to Anahuac to attempt to rebuild the fort and collect tariffs. But a Texian force led by Travis attacked from the sea and on June 30, 1835, before any fighting had begun in earnest, the Mexican force surrendered. The Mexican government demanded that the Texians give up Travis for a military trial, but they, of course, refused.

By the end of the year, the Texas Revolution was in full flame. After Texas won its independence in 1836, local residents hauled away most of the bricks from the Fort Anahuac ruins and put them to other purposes. Eventually, even the fort's foundations were buried and forgotten.

The Excavation

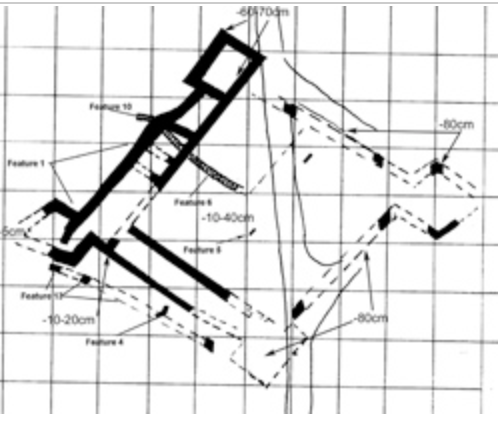

In 1968, several years after the site had become part of a Chambers County park, a group of amateur archaeologists did a haphazard excavation at the site, but no serious archaeology was attempted until 2001, when the county government asked the Texas Historical Commission to survey the park with a magnetometer to try to ascertain the fort's exact location. The magnetometer found the foundations of about half the fort – enough to determine that it had been diamond-shaped — and one of its bastions.

Texas Historical Commission archaeologist James Bruseth recommended to the Chambers County commissioners court that it conduct archaeological testing to determine how much of the fort could be found and preserved. He also recommended the construction of an interpretive museum and, perhaps, a replica of the original fort. The county engaged Hicks & Company, an Austin environmental consulting firm, to test the site.

"Our test excavation confirmed what everybody suspected the configuration of the fort was," says Rachel Feit, the Hicks archaeologist who directed the work. "We found a number of construction techniques."

"One wall in the plaza was constructed of brick rubble. We don't know what it was, whether it was a corral or a hospital. We found a series of brick-lined aqueducts or drains that would have been built below the surface of the plaza. Recent excavations have revealed that these features were designed to drain water away from the fort, rather than catch water within it."

Since souvenir hunters had picked over the site for so many years, the archaeologists initially found few artifacts to offer clues to the functions of the fort's various structures. However, the most recent excavations did reveal a well-preserved outbuilding feature with an intact floor surface.

Artifacts picked up from this surface included a large number of cut nails, ceramics, a gun flint and a Mexican uniform button. The building is thought to have had wood-frame walls and featured a front porch facing the water. Archeologists believe that it might be a customs house or the jail.

Beanie Rowland, chair of the Chambers County Historical Commission, says the county is trying to raise grant money for further archaeology and to draw up architectural plans for the proposed museum.

"Anahuac was important to Texas history," she says. "We want to show schoolchildren where the first shot of the Texas Revolution was fired. We want them to be able to imagine, looking out over the bluff, that first customs house on the Trinity River. We want to let them relive our history."

— written by Bryan Woolley, senior writer for The Dallas Morning News and a novelist, for the Texas Almanac 2004–2005.