Texas Water

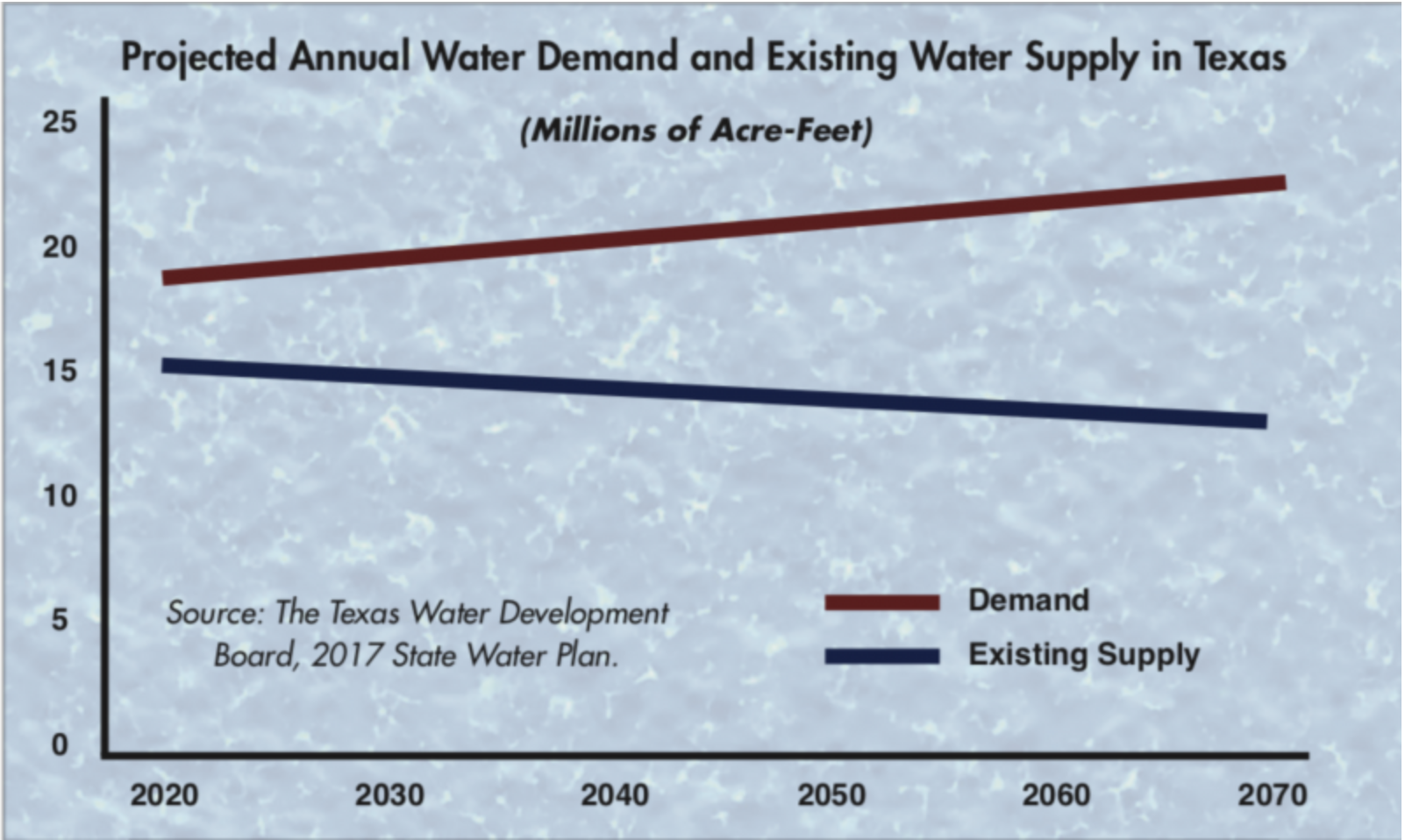

No natural resource has greater significance for the future of Texas than water. In Texas, the population is expected to essentially double in the next generation, and yet, we have already given permission for more water to be drawn from many of our rivers than is actually in them.

Although there are many proposed strategies designed to meet our future water needs, none is more urgent than educating the coming generation of the value of water and its crucial impact on both economic prosperity and the environment in the years ahead.

A Longstanding Problem

Though serious droughts in the first decade of the 21st century have brought greater attention to Texas’ daunting water problems, these issues have been developing over many years. The state’s impressive system of reservoirs was built in the years following what is officially known as the “drought of record,” seven years in the 1950s that the Texas Water Development Board (TWDB) defines as “the period of time during recorded history when natural hydrological conditions provided the least amount of water supply.”

In those years, most Texans lived in small communities with agricultural economies or on the land itself as farmers and ranchers. In this mostly rural environment, the majority of the state’s inhabitants felt the drought directly and personally. In response to such direct impact, Texas leaders launched an extensive water infrastructure development program and water planning system that we still rely on today. Because most Texans now live in a few large urban areas, the effects of drought are not as painful or immediate.

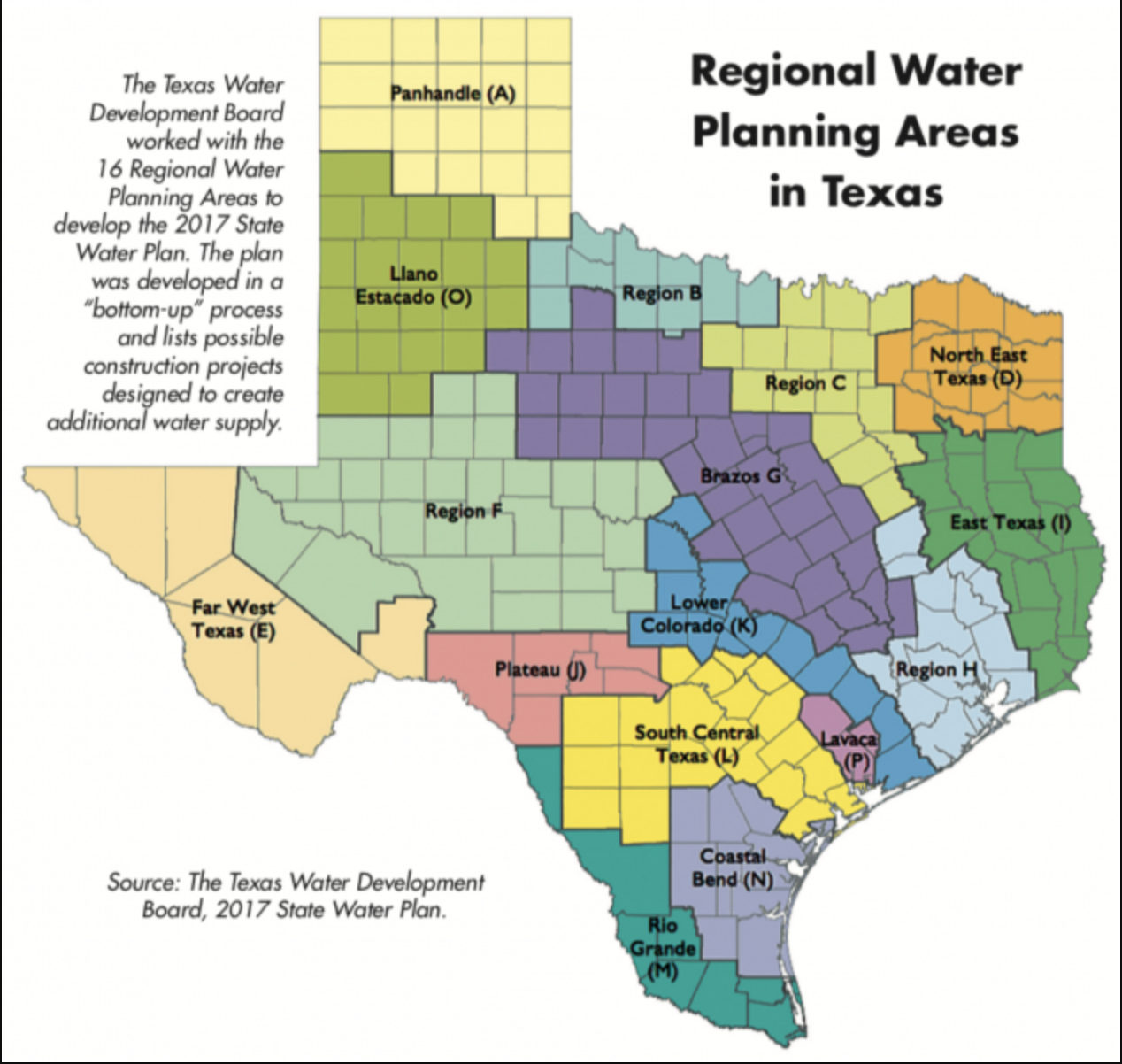

In addition to the public’s lack of awareness of the serious water dilemma Texas faces, the issue itself has become much more complex. The Texas State Water Plan issued by TWDB in 2017 was created in a “bottom-up” process involving 16 regional planning groups and is largely a wish list of proposed construction projects designed to create additional water supply. The estimated cost of the plan is $63 billion. The facts are that even if state leaders can find a way to generate that amount of financing, the reality of other water challenges is such that we simply cannot build our way out of them. These challenges include:

- one

- two

- three

Ironically, even against this backdrop, here in Texas, we have been successful in managing our natural resources, including water, over the past century. According to Dr. David Schmidly, president of the University of New Mexico and author of Texas Natural History: A Century of Change, our landscape, including our watersheds, is in much better condition today than it was prior to the turn of the 20th century.

Following the Dust Bowl period of the 1930s, an entire generation of landowners was educated and inspired to a more enlightened stewardship, thanks to the efforts of government agencies, such as the Agricultural Extension Service, now known as the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension, and the Soil Conservation Service, now known as the Natural Resources Conservation Service. In Texas, approximately 95 percent of our landscape is privately owned, and thanks to the efforts of these private land stewards, the condition of that landscape and, thus, our watersheds and recharge areas has greatly improved. Partially as a result, our water quality has improved, as well.

Significantly, the passage and implementation of the federal Clean Water Act of 1972 also dramatically improved the water quality in our rivers and streams, which, until the late 1960s, were often contaminated with poorly treated or completely untreated industrial and municipal waste. In spite of these successes, Texas must confront serious challenges related to water, and education will be a key strategy for doing so.

With respect to the nexus between our water resources and the landscape in Texas, it is an important fact and insight that the state is almost entirely owned by private citizens and, thus, virtually all of our watersheds, flood plains, and recharge areas are on private property. Experts argue about the exact percentage of land in private ownership, but it is indisputable that somewhere between 94 percent to 97 percent of the Texas landscape is privately held.

The Price of Urbanization

The implications for the environment, and water resource management in particular, are profound. Texas has become one of the most urbanized states in the country and, as a result, loses increasing amounts of rural and agricultural land each year – faster, in fact, than any other state. This accelerating urban encroachment, combined with the pressure on heirs who are often left with as much tax burden as land, contributes to an inexorable process of land fragmentation. That fragmentation is the single greatest terrestrial environmental problem Texas faces today, and it is directly related to the state’s water problems, as well.

As the average size of tracts of land in Texas continues to diminish, the function of our watersheds is irrevocably impaired for both the economic and environmental future of the state. In fact, the issues associated with ensuring sufficient clean water for economic growth and the environment is the most significant and urgent environmental concern facing Texans in the next generation. There are several significant insights that are key to our understanding the issue.

For example, most of the available water in Texas is in the eastern part of the state, where rainfall is upwards of 60 inches per year and growth is essentially flat. Conversely, most of the current and expected economic growth is along the Interstate 35 and Interstate 45 corridors, where rainfall can be as low as 25 inches per year.

Over the years, there has been much talk of moving large amounts of water westward from eastern rivers to thirsty cities, farms, and industries, but regional competition, environmental objections, and substantial legal impediments have thus far kept this from happening on a major scale. Nevertheless, water planners, policy makers, and utility managers will continue to attempt to find ways to move water westward in the years ahead, and decisions related to these attempts will require an informed and engaged citizenry, as such proposals are inevitably controversial.

Surface Water Shortfall

Such enormous and far-reaching projects have their origin in the fact that historically, we have largely depended on surface water for human uses, including agriculture, industry, municipal consumption, and recreation. Surface water occurs naturally in rivers and streams and is now stored in 188 major reservoirs – one of the most extensive impoundment systems in the United States. According to the 2017 State Water Plan, a major reservoir is one that has at least 5,000 acre-feet of storage capacity as its normal operating level. An acre-foot is the amount of water required to cover one acre of land with 12 inches of water.

By law, the water in our rivers is considered the property of the people of the State of Texas. Today, most of that water has already been spoken for through a system of water-rights allocation administered now by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality but that has its origin when Texas was a colony of Spain. In fact, some of our rivers have actually been over appropriated during this long history. That is, if all of the water permitted to be used from them were to be withdrawn, they would dry up.

A vivid example of this frightening possibility was made all too clear in the first decade of the new century when, for a time, the Rio Grande no longer reached its mouth on the Gulf of Mexico. As much as 85 percent of the water in our rivers and streams has been allocated to agriculture, thus rendering its availability for urban development, industry, and the environment very difficult.

Compounding this problem is the fact that the state has not constructed a new reservoir in more than 20 years. The most recent is Jim Chapman Reservoir on the Sulphur River, which was dedicated in 1991. There are simply not many sites left in Texas where reservoirs can be built, and those sites that do exist often contain important biological resources that would be destroyed by reservoir construction, including much of the state’s remaining bottomland hardwood forests and significant fish and wildlife habitats.

A prominent example was the proposed Fastrill Reservoir on the Neches River. The City of Dallas and the TWDB supported the construction of the massive reservoir, but in 1985, the area was identified by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as a Priority One Conservation Area and favored the development of what is now the Neches River National Wildlife Refuge. A multi-year court battle went to the U.S. Supreme Court in 2010, with the wildlife refuge coming out on the winning end.

The latest of the state’s water plans, which are issued every five years, envisions 26 new major impoundments; however, there are significant environmental concerns about many of these projects. Finally, private landowners in Texas have become increasingly politically aggressive in resisting the taking of private property for reservoir construction through eminent domain. In sum, all of these factors make the process for approving, financing, and constructing reservoirs a challenge that can take many years to complete.

Protecting Aquatic Life

Another important factor constraining the use of surface water is that the state has historically provided very little protection for what are called “environmental flows,” which are the amounts of water necessary to sustain aquatic life in rivers and in the bays and estuaries into which the rivers flow. “Instream flows” are essential to support freshwater aquatic life in the upper reaches of river systems, and “freshwater inflows” help maintain the health of our bays and estuarine systems.

The Texas Legislature did not officially recognize that protecting the aquatic environment was a beneficial use of water until 1985 when, for the first time, fairly modest provisions were included in water rights permits issued by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality to protect environmental flows. By that time, unfortunately, the vast majority of Texas’ surface water had already been permitted for use and thus not available for environmental purposes.

Recognizing both the environmental and political consequences of this dire situation, a collaboration of conservation groups launched the Texas Living Waters Project in the 1990s to educate decision-makers and the general public about the environmental and economic impacts of wasteful water development and the availability of cost-effective, environmentally sound alternatives.

This major initiative was ultimately successful in 2007 in encouraging the Legislature to lay the groundwork for protecting environmental flows.

From an ecological standpoint, if we are not able to sustain the flow of freshwater to our bays and estuaries, their biological productivity will decline substantially. These areas provide not only the best coastal sport fishing in the country but also billions of dollars in annual economic benefit to the state through waterfowl hunting, bird watching, and the commercial harvest of oysters and shrimp.

Largely as a result of these many daunting challenges to Texas’ limited surface water supply, the state is increasingly looking at groundwater as its principal source.

The Aquifer Enigma

Groundwater use in Texas is not a new concept. San Antonio, for example, has historically been 100-percent dependent on groundwater from the Edwards Aquifer for both industrial and municipal use. A primary reason is that for nearly 100 years, Texas did not regulate groundwater use in any way.

A Texas Supreme Court decision in the early 20th century declared that groundwater was too “mysterious and occult” to understand and thus to regulate. Since then, the rule for groundwater use in the state has been the “right to capture,” meaning that anyone owning land above a subterranean water source can pump an unlimited amount of water for any purpose.

This total lack of regulation for groundwater is in stark contrast to the very heavy regulation of surface water and is the primary reason that entrepreneurs in various parts of the state, including the Panhandle, Trans-Pecos, and Post Oak Savannah regions, are feverishly attempting to secure and market very large volumes of water from the aquifers below. Among these entrepreneurs are such titans as Boone Pickens and Clayton Williams.

A complicating factor is that Texas’ nine major aquifers and twenty-one minor aquifers are very different hydro-geologically. Some of these underground reservoirs, including the Edwards Aquifer which lies in very porous limestone, recharge themselves fairly regularly, while others were charged as long ago as the Ice Age and do not replenish. In recent years, the Texas Legislature enabled the establishment of local groundwater conservation districts to begin bringing some semblance of order to groundwater use.

Many of these districts, however, are problematic. They are organized along county lines rather than the natural boundaries of the aquifers, are poorly funded, and lack either the fundamental science or the expertise to do their jobs. Complicating these impediments is the fact that citizens affected by the actions of these districts are often uninformed of their activities and don’t participate in elections for their leaders.

Most scientists concur that there are substantial groundwater reserves available that directly affect and even maintain our surface waters through spring flow. But managing these resources will be ineffective unless there is more participation by groundwater conservation districts, greater public education, and laws and policies linking groundwater and surface water.

Dealing with Drought

Traditionally, it has taken a crisis in Texas to spur politicians to address the state’s water problems. Much of the existing water infrastructure and the planning process on which the future of the state depends came in the wake of the drought of record in the 1950s.

According to Dr. John Nielsen-Gammon, the Texas State Climatologist since 2000, that period from 1950 to 1957 is the most severe drought overall that Texas has experienced. So devastating was this drought in terms of duration, it inspired the late, award-winning author Elmer Kelton to pen his historical novel The Time It Never Rained (1973).

But in 2011, Texas experienced another extreme drought that caused wells to go dry, wildfires to break out across the state, and reservoirs to decline. In fact, July 2011 was the warmest month ever recorded statewide in Texas, and 2011 was the hottest summer on record.

One especially severe wildfire was the Bastrop County Complex Fire. It began Sept. 4, 2011, as three separate fires and merged into a single blaze east of the City of Bastrop. It eventually spread over 34,000 acres of land, killing two people and destroying 1,691 homes and much of Bastrop State Park. When it was finally extinguished on Oct. 29, it was declared the most destructive wildfire in Texas history.

Another massive fire complex raged from April 9–13, 2011, near Possum Kingdom Lake in Palo Pinto County. Severe drought that began in 2010 and critical fire weather that occurred for several days helped spark the inferno, which began as four separate fires. High winds brought the fires together and helped it spread for 16 days before it was contained. The fires burned 167 homes, 126 other buildings, and 90 percent of Possum Kingdom State Park — a total of 126,734 acres. Property losses were estimated at $120 million.

In response, the 83rd Legislature and Texas voters, through a 2013 constitutional amendment, created the SWIFT program – State Water Implementation Fund for Texas – which provides $2 billion from the State’s Rainy Day Fund for low-interest loans, extended repayment terms, and other incentives for developing and optimizing community water supplies.

It was yet another drought in the 1990s that sparked a spate of water-related laws that provided the context for addressing Texas’ future water needs in this century. Senate Bill 1, passed in 1997, is considered a landmark piece of legislation. Its centerpiece was the creation of the bottom-up planning process that involves local interests and stakeholders in regional committees, replacing the old centralized planning system that came into being after the drought of record.

Unfortunately, when these regional planning groups were established, many of our river basins were divided, making systemwide planning very difficult. In addition, interest in the process varied widely. Some regional groups consider environmental issues important, while others have ignored them completely, rendering their decisions ineffective at best and destructive at worst. Clearly, the bottom-up process, to function effectively, depends on participants who are informed, motivated, and representative of all stakeholders and points of view.

More Legislation

As Texas has continued to urbanize, another disturbing trend is the increasing lack of consideration for issues of concern to rural areas and small towns. Dallas, for example, seeks to impose unwanted reservoirs on East Texans, and San Antonio continues its reliance on the Edwards Aquifer, threatening spring flows in New Braunfels and San Marcos and the water supplies of downstream communities, including Seguin and Victoria.

The planning system put in place through Senate Bill 1 demonstrated that groundwater would have to play a much bigger role in the future and, as a result, its management became the basis for Senate Bill 2.

This second major piece of legislation, enacted in 2001, enabled the creation of the groundwater conservation districts, thus amending the rule of capture for the first time in a century and, theoretically, placing some limits on it.

Finally, in 2007, the Texas Legislature took another bold step and established, for the first time, a process for protecting environmental flows in the state’s rivers and streams with Senate Bill 3. The law allowed for the creation of stakeholder committees and expert science teams to be named for each bay and basin to recommend environmental flow standards to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality.

Today, thanks to the increased public participation mandated by these laws, continued population growth, persistent drought, and the obvious fact that some of our most important sources of water are increasingly limited, water remains in the forefront of public policy in Texas. Unfortunately, for most of our citizens, especially Texas children who will be the leaders of tomorrow, as long as water continues to flow from the tap, the perception is that there is no problem. In this context, water conservation is absolutely essential.

Looking to the Future

One of the most promising ways to extend our supplies of water is through increased efficiency and conservation in both agricultural and municipal use. The cities of San Antonio and El Paso have made major strides in water conservation, decreasing per capita consumption of water by as much as 40 percent, while consumption in other Texas communities has continued to grow.

Certain agricultural sectors, particularly in the High Plains, have dramatically improved the efficiency of irrigation practices, while consumption in other farming communities, particularly citrus, is way behind. Many cities and water authorities are looking closely at re-use of treated wastewater, which, while intuitively logical, could cause problems for communities and interests downstream that depend on return flows.

Finally, looming over all these issues is the fact that all modern water planning in Texas for the past half century has been based on the notion that the drought of the 1950s is as bad as it is going to get. Today, with the widespread consensus that the climate is indeed changing as a result of both natural and humaninduced phenomena, such thinking is outdated and unhelpful. Examination of fossil records, tree rings, and ice cores from the poles demonstrates that climatic extremes far greater than previously envisioned may well be experienced by humanity in the coming decades.

Educated consideration of climate change is essential in the discussion of future water resource planning and management in Texas, despite the fact that recent state water planning has minimized or ignored it. Anticipating the uncertainties of climate change will help us prepare more thoughtfully for the future.

Ensuring that there are water resources in Texas that can help meet our needs requires that we plan wisely, and we now have a process in place that is transparent and dependent on public participation. It is up to us to be educated, informed, and engaged. The future of our children may depend, in large measure, on their water literacy.

One thing each of us can do is to take the time during the year to introduce a child to water in the outdoors. Whether we take them fishing, kayaking, swimming, or any one of the many recreational activities water affords us, we need to help them understand that our water is a constant source of joy and inspiration but is essential for all of life, and they must learn to take responsibility for it.

— written by Andrew Sansom, leading conservationist and serves as research professor of geography and executive director of The Meadows Center for Water and the Environment at Texas State University in San Marcos..