The building in San Antonio we call the Alamo originally was built as the chapel of the Mission San Antonio de Valero.

Valero mission was established at San Pedro Springs in present-day San Antonio in 1718 by Fray Antonio de San Buenaventura y Olivares, a Franciscan missionary of the College of Santa Cruz de Querétaro.

Like all Spanish missions, Valero was a combination of religious and industrial trade school for Indians. For several years, the mission consisted of several huts and a small stone tower, which were destroyed by a storm in 1724. Mass was celebrated in temporary quarters until the first stone church building was constructed about 1744. This building collapsed about 1756. The second stone chapel, begun about 1758 and never completed as a chapel, stands today in Alamo Plaza.

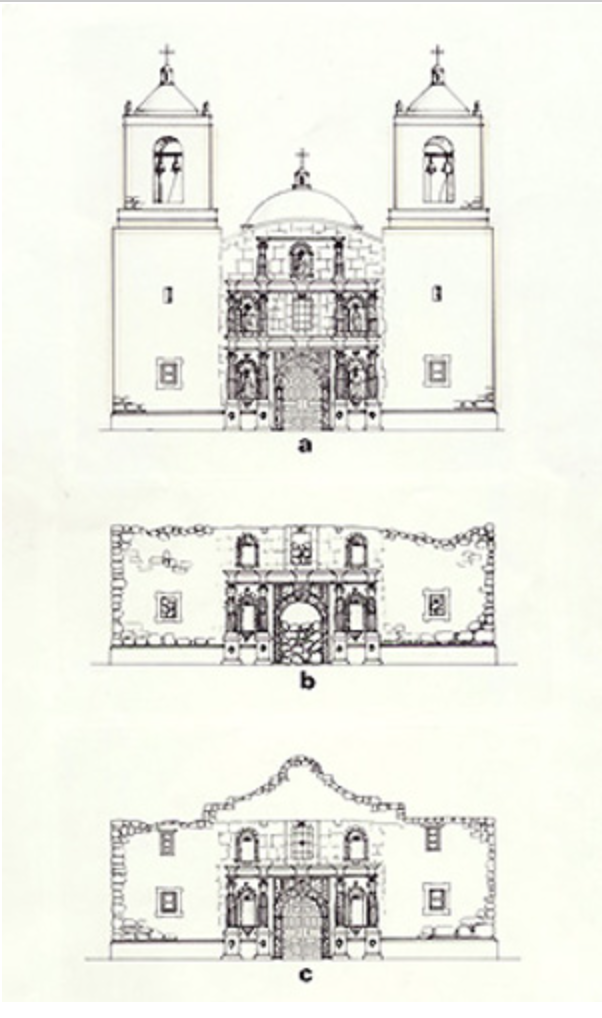

Cruciform in shape and 35 Spanish varas (more than 90 feet) long, the chapel has a large nave and a broad transept. The walls, built of local limestone blocks, are more than 3.5 feet thick. The floor was probably paved with flagstones. Study of the original part of the building indicates that the chapel was to have twin bell towers, with a dome over the center of the building.

The mission complex once covered up to four acres of ground and contained not only the church, but also the convento, or priests' quarters; a granary; workrooms; storerooms; and Indian housing, all surrounded by an outer wall.

By 1778, disease epidemics had depopulated Valero, as well as the four other missions that had subsequently been established in the vicinity, to the point that not enough Indians were left to work the fields. In 1793, Valero was converted into a self-supporting parish church.

After the conversion, the still-unfinished Valero chapel was stripped of usable doors, windows and hardware. It served at times as a parish church for soldiers who were stationed there, and it became San Antonio's first hospital from 1806 to 1812.

The Valero mission building came to be known as the "Alamo" when a company of cavalry -- called the Segunda Compañía Volante de San José y Santiago del Alamo de Parras (Second Flying Company of San José and Santiago of the Alamo of Parras) -- was stationed there for more than 10 years, beginning in 1801 or 1802. The town of San José y Santiago del Alamo de Parras in the Mexican state of Coahuila was where, in the 1780s, the unit had been recruited. As tradition dictated, the company was identified by the full name of the town. "Alamo" is the Spanish word for cottonwood. "Alamo" in the town's name is thought to refer to a landmark cottonwood tree growing on a ranch near Parras. The mission chapel is still called the Alamo; the town of Parras, however, is now called Viesca.

Its Role in the Texas Revolution

To many Texans, of course, the most important use of the Alamo was as a fort during the Texas revolution. Mexican Gen. Martín Perfecto de Cos used the Alamo as his headquarters in San Antonio. In preparation for the Texan assault in late 1835, Cos tore down the chapel's arches to use as ramps for hauling cannon to the tops of the walls. And the climactic 13-day siege and battle of the Alamo in 1836 was all-important in turning the tide of the Texas revolution.

The Present Alamo Building

The signature scalloped roof line of the Alamo was not part of the building until 1849. It was added by the U.S. Army when it leased the former chapel from the Roman Catholic Church to use for storing hay and grain. The two outer windows on the upper level also were added at that time. Many representations of the building in paintings, drawings and movies wrongly show these late additions as part of the building during the 1836 battle. An army artist who sketched the Alamo compound in 1849 after the remodeling commented that the chapel had been topped with "a ridiculous scroll, giving the building the appearance of the headboard of a bedstead." Of the present Alamo building, probably only the bottom 23 feet of wall are part of the original.

The Alamo changed hands at least 16 times among Spanish, Mexican, Texan, Union and Confederate forces between 1810 and the end of the Civil War. During the early 1840s, stones from the Alamo were hauled away by scavengers. Development began creeping onto the former mission's grounds in the 1850s.

When a supply depot was built at Fort Sam Houston in 1878, the army left the Alamo compound, and merchant Hugo Grenet purchased the convento (also called the long barracks) from the church, remodeling the property to house a retail store. He leased the chapel for use as a warehouse. Grenet's renovations gave the convento the appearance of a crenelated medieval castle. After Grenet died in 1882, the mercantile firm of Hugo & Schmeltzer purchased the convento; the chapel reverted to the church, which sold it to the state in 1883.

Saving the Alamo Complex

In the 1890s, Adina de Zavala, granddaughter of Mexican-born Texas patriot Lorenzo de Zavala and first vice president of the Daughters of the Republic of Texas (DRT), extracted a promise from merchant Gaston Schmeltzer that he would sell her the convento building for $75,000. But her fund raising stalled short of the goal. In February 1904, Clara Driscoll, from a wealthy San Antonio family, advanced at no interest the $25,000 needed to hold the convento until the Legislature appropriated the purchase price. She was partially reimbursed by the state in 1905, and the Legislature entrusted both convento and chapel to the DRT. [Ed. nogte: In 2011, the state General Land Office took ownership of the Alamo, and in 2015 it took over management of the facility.] Although Driscoll is called the "Savior of the Alamo," the Alamo itself already belonged to the state. What Driscoll saved was the convento.

De Zavala and Driscoll fought over the best way to preserve the site. De Zavala wanted both chapel and convento restored to demonstrate the site's original purpose as a mission. Ironically, Driscoll, who had saved the convento, wanted it demolished, so that the chapel's role in the Texas revolution would be emphasized. A public hearing was held in December 1911, during which de Zavala offered documentation as to the importance of the convento. The convento was saved.

In its almost 300-year existence, the Alamo has played many roles. It has served as the chapel of a Spanish mission; quarters for troops; housing for Indians, Tejanos and squatters; hospital; army supply depot; Masonic lodge; jail; commercial store and warehouse; public park; tourist attraction; movie set; and historic site. To Texans, however, it will always be "The Alamo — Shrine of Texas Liberty."

— written by Mary G. Ramos, editor emerita, for the Texas Almanac 1992–1993.